Ebeth Scobbie married at 28 and was widowed at 33. As Mrs Ebeth Newton, she married again at 46, to a successful and well-regarded Edinburgh solicitor, Robert Galloway, also a widow. He was 69. Their wedding in 1930 was at Greenbank Church (near Robert’s home) in the south of Edinburgh, the capital city of Scotland.

I assume Ebeth and Robert found happiness with each other – they had just each lived through a dozen or so years of widowhood, right through the 1920s. I wonder if their ages were a big talking point back then: there was a 23 year age gap, which I assume was unusual. Is that Angus (Robert’s son) scowling in the background?! Or does just he just have a serious face? Well, Angus was just 11 years younger than Ebeth… and they were in the same generation, given that they had both “seen action” in the war. Maybe he was uncomfortable.

Here’s the full picture… Ebeth’s daughter Elizabeth looks the happiest. She was 14. (In the background, patriarch James Scobbie,who was 77.)

Ebeth’s address was given as 1 Riselaw Road, nearby.

Greenbank Church

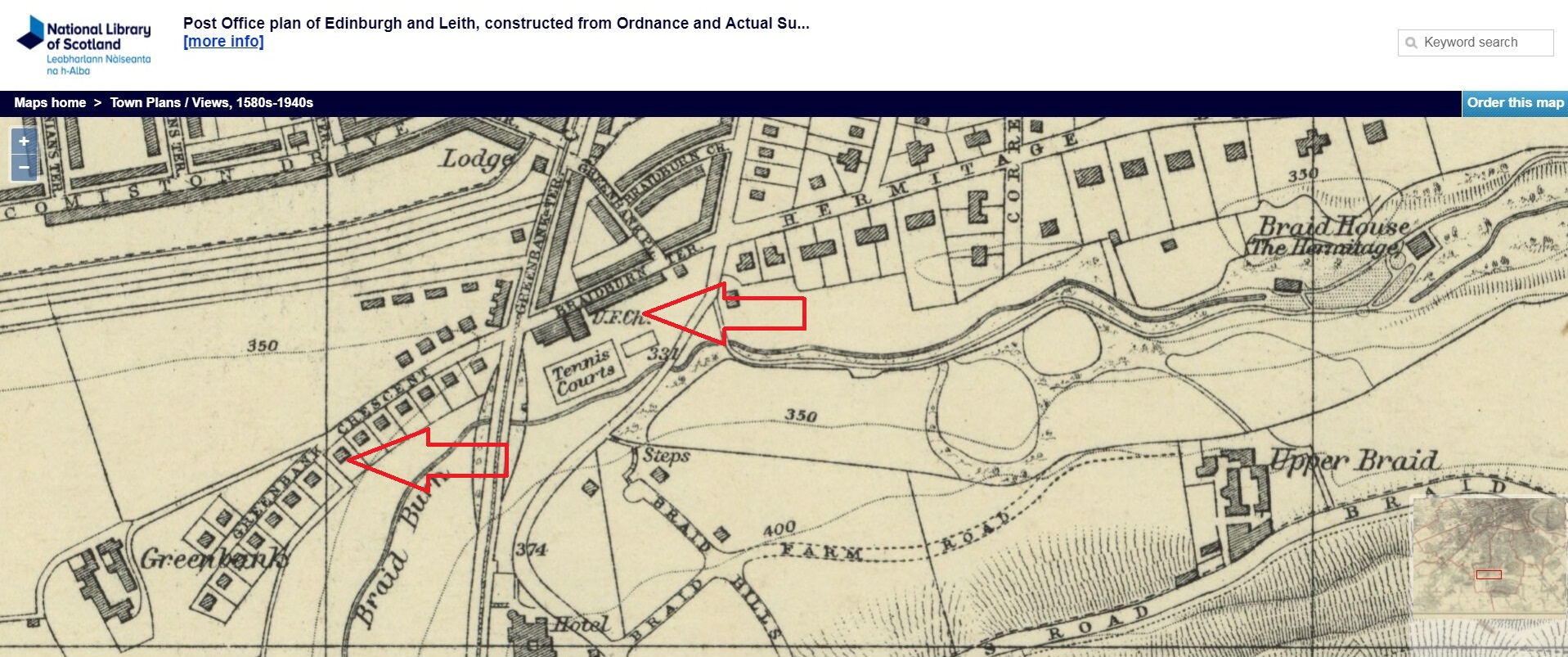

An almost incidental aspect of this wedding is where the wedding took place: Greenbank Church. It’s still there, a local landmark (like most churches and pubs), now at a busy junction. When built, it was on the very southern boundary of Edinburgh, just north of the Braid Burn, on the main road south to Fairmilehead, Penicuik, and beyond. Robert lived in a traditional Victorian semi-detached villa a stone’s throw away, at 23 Greenbank Crescent (next to the Fly Walk, and arrowed in the image below). The newer housing in that area (starting to the south of the church across the Braid Burn glen on the slopes of the Braid Hills, extending Greenback Crescent down towards Oxgangs, and opposite their house north towards Comiston Drive) is nearly all “between the wars” style, so there must have been a great deal of construction in the (20s &) 30s, as can be seen in the map, where the new Braid Farm Road is just being marked out. You can view these houses on Google Streetview of course, or look in the page about Ebeth’s daughter Elizabeth (Dr Elizabeth McKenzie Mitchell nee Newton, 1916-2011) for a quick view.

Ebeth’s elder sister Mabel Logan (Mary Black Laughland Scobbie, 1879-1970) had (I think) been living in the semi-detached villa 8 Hermitage Drive (below the “R” of “Hermitage) ever since her marriage aged 19 in 1898 to (the older) John Hunter Logan (1860-1933), a coal master like Ebeth and Mabel’s father.

The main church building was itself relatively new (1927), though the congregation had been founded in 1900. Robert Galloway was at some time an elder and session clerk of the church. The minister (who officiated at their wedding) was Dr T. Ratcliffe Barnett (in post from 1913-1938). He had been in the United Free Church until its union with the Church of Scotland in 1929. More importantly, he was highly dynamic, charismatic and educated. Barnett published a number of books, on topics including folk tales, Celtic mysticism, and descriptions of people, place and history in Scotland. His PhD (in English Literature) from the University of Edinburgh was on Queen Margaret and the influence she exerted on the Celtic Church in Scotland (1925). Also, in 1917 he had introduced Wilfred Owen to Ivor Gurney, during his work as a hospital chaplain in the Edinburgh War Hospital in Bangour, west of Edinburgh (now just north of the M8 as it passes Livingston), a post he took up because of his own war experience and that of his parishioners.

Wilfred Owen

Owen (1893-1918) is perhaps the most famous of the war poets. He was killed in action on 4th November 1918, 99 years ago (as I write), a week before the armistice. Gurney (1890-1937) was a also a war poet, but in addition he was a composer and musician with great promise. Sadly, mental illness associated with his bi-polar personality and his wartime experiences led to him being committed to an asylum in 1922, from which he was never released. He died 15 years later. Gurney’s book of poems was published in 1917.

Owen had arrived in Edinburgh (to the hospital at Craiglockhart, on the western fringes of Morningside, near Greenbank) on 25th June 1917. In August he met the poets Siegfried Sassoon and Robert Graves. Activities (including writing) were greatly encouraged at Craiglockhart, and Sassoon encouraged and helped Owen develop what was at that point an amateur talent and hobby, and in particular and most importantly, he advised Owen to write about the war, something that fitted well with the rehabilitative regime, and which Owen had thought inappropriate. Thus, by October, Owen had written both Anthem for Doomed Youth and Dulce et Decorum Est. In November, he was discharged.

Owen was little known in his lifetime, but now has a monumental reputation, and his association has made Craiglockhart well-known too. (It has been a hydropathic sanatorium, part of Napier University, and now is in the centre of a housing development. There is a small war poet museum.) Regeneration, the first book in a trilogy by Pat Barker, presents the relationship of Sassoon and Owen in Craiglockhart in context, and was filmed in 1997 by Gillies MacKinnon. In this scene, Owen and Sassoon meet. A theatrical adaptation of Regeneration toured the UK in 2014.

It was only after Owen’s death that Seigfried Sassoon (who had been shot in the head, and survived) ensured Owen’s poetry would be posthumously published.

A number of events in 2017 in Edinburgh marked the centenary of this crucial meeting without which the following, for example, would certainly not exist.

Anthem for Doomed Youth

Dr T. Ratcliffe Barnett

Rev. Barnett was a key part of this world. An account of Barnett, and of his links with Owen & Gurney by Pamela Blevins is available (taken I think from her biography of Gurney). Here is an evocative moment, from the very week in which both Owen and Gurney were discharged back to active service in November 1917, a century ago:

Ratcliffe Barnett invited Gurney to play the piano for officers at the Edinburgh War Hospital. He performed an ambitious programme of Beethoven, Bach and Chopin and was pleased to report to Marion Scott that the officers “listened beautifully” while “Mr. Barnett…listened in a pure ecstasy.” Gurney had copied out “By a Bierside” for Barnett who insisted that he sing it for him along with “The Folly of Being Comforted”. The evening was a great success and Barnett returned home to Morningside full of joy.

By a Bierside is a poem by John Masefield, set to music by Gurney. These “songs” are not my cup of tea I’m afraid. I prefer Gurney’s orchestral A Gloucestershire Rhapsody.

A memorial to four interlinked lives

They only had five simple years together. After his accident in 1935, Robert died the next year. Ebeth died in 1940.

When preparing these short articles on Ebeth, I already knew that the couple were buried in Morningside Cemetery, but it’s a big place, and there are many fallen or corroded stones. Thanks to the help of the Friends of Morningside Cemetery, I was pointed to the index (in the local library), and was able to visit and say hello. Rather sweetly, the gravestone memorialises not just Ebeth & Robert, but also Robert & Agnes, and Ebeth & David.

This is a romantic and fitting tribute to love and death. Who knows what people who believe in an afterlife had to say about how Robert and Ebeth split their eternity between the various spouses! I am not impressed by supernaturalism or the spurious conjectures it prompts. The realities are powerful enough:

- people can find more than one soul-mate in a lifetime

- some of us have long and happy lives, and others not

- you can never predict with certainty what will happen

Statistics and demographics provide some clues about wealth, health and happiness, but general trends matter nothing when you are unexpectedly the one in the wooden box. Even so, warfare played a big part in cutting short the lives mentioned here, whether from bullets, bombs or disease, and is, I think, something that can now be avoided, more often than not. There’s another moral.

One stanza from the 1914 poem by Robert Laurence Binyon will end this piece on an note that is most appropriate for a blog written around Remembrance Day in November. I am thinking of civilians and victims of all kinds, not just servicemen, when I read:

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

Morningside Cemetery

The grave can be found using the map below, because the index showed that its location is in section J, plot J002, in the south east corner. “001” is clearly marked on the plan, so the grave is easy to find.

Sadly, the stone has fallen over (see below).

Other pages (good starting points for Ebeth, then more Morninside)

- 19th Century Morningside

- A Morningide Tenement

- The Plasterer’s Flat

- The Aitkens’ Coin-Glass Goblet

- Woodburn House’s MP for Leith, MacGregor

Sources and Resources

Shelia B Durham (1981) Index to Morningside Cemetery (2 vols). In Morningside Library.

Friends of Morningside Cemetery Facebook page

Website (Accessed 11/11/2017) Wikipedia page on Morningside Cemetery

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Morningside_Cemetery,_Edinburgh

War Poet Wilfred Owen A Remembrance Tale. BBC Documentary, available online (11/11/2017) at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tUTnf8Ry1Vg

Pamela Blevins (2008) Ivor Gurney and Marion Scott: Song of Pain and Beauty. The Boydell Press. [not consulted]

Harriet Richardson (2016) Historic Hospitals, Edinburgh (accessed July 2018). Website. https://historic-hospitals.com/gazetteer/edinburgh/ [not used but very nice for local information]

National Library of Scotland maps – https://maps.nls.uk/view/109707821 (accessed July 2018) [copyright information at https://maps.nls.uk/copyright.html ]

OpenStreetMap (accessed 2017) shows excellent detail in this area and is open access. Here is the contemporary view corresponding to the 1929 map above.

Very interested in your posts could I think add some corrections!

LikeLiked by 1 person

oh yes that would be very helpful. I will email you.

LikeLike