My aunt’s family history is convoluted, complex and interesting, the complexity providing a good training in genealogy. Some elements are stark and simple. The death of her mother’s first husband in WW1, the “Great War”, and of their son, her (half) brother in WW2… they were both killed in action. That’s pretty straightforward. You’d think.

It took a while, but now I know who’s who. I still know nothing personal about these men. Nor their lives before or during the wars that killed them. I am not really related to them (my mother’s sister-in-law’s mother’s first husband & son) in any clear way. But the centenary of the armistice in 1918 is a good time for a minding, and for me to mind them in particular. And some others. We are all connected. Me the writer; you the reader; and the dead. I know these soldiers’ bare details, a little general context, and something about what happened to those they left behind, but apart from that… their personalities, hopes and dreams? They are unknown to me. But here they are.

Searching

Since 1855, a Scottish wedding certificate has given the names of the parents of the couple being married, their ages, possibly the date of marriage of the couple’s parents, and whether they are still alive. As well as location, it also provides parental (father’s) occupation (and names of witnesses, celebrants, registering officers). Researching my aunt’s wider story started with the wedding certificate of her parents James Munro and Charlotte Grubb, who married on 18 April 1919 in Rothes. It gave three surnames for Charlotte, because she had been widowed. Her first husband had the surname Taylor. Before that, her original surname (so-called maiden surname) was given as Grubb.

One of the several challenging and satisfying aspects in working out her family story and that of others linked to her around Strathspey in the eastern Highlands of Scotland,[1] an area famous for agriculture and whisky, was that even all this detail did not lead directly to what should have been her easy-to-find birth certificate. This was because her birth was registered under her mother’s surname Cruickshank, not the surname the family adopted later, that of her step-father, James Grubb. Also, though Charlotte she said was 27 in 1919 on her marriage certificate to James Munro, she was actually 29. More on that and more another time. The focus here is one specific person, who I have chosen as the topic of a post to mark the centenary Armistice Day, in 2018.

Archibald Taylor (1892-1918)

Charlotte Grubb’s first, short, marriage, was to Archibald Taylor. They married on 1st June 1915, at 37 Land St., Rothes, the Grubb parental home. Both had been living in Parkbeg, Dufftown and presumably met there. Their marriage certificate says Charlotte was 25 and a domestic servant, while Archibald was 23 and a farm servant. His parents were James Taylor, general labourer, deceased, and Annie Grant. Parkbeg was just east of Dufftown and Balvenie Castle, across the River Fiddich, but no longer exists. Parkmore Farm does. Beag and mòr in Gaelic mean wee and big respectively.

Charlotte’s surname and father’s details on this wedding certificate don’t fit with the details on her 1890 birth certificate for one very good reason: no father is named on her birth certificate. However, these details differ also from her second marriage certificate, nearly four years after the first, after Archibald’s death. Her father would be given in 1919 as her step-father James Grubb. At her marriage to Archibald her father is named as Alexander Stewart, general labourer, deceased, who was presumably her biological father. In both marriage certificates, her mother is named as Maggie Grubb, maiden surname Cruickshank, and on Charlotte’s birth certificate (10th Feb 1890, in Inveravon, Banffshire), her mother is given as Margaret Cruickshank, pure and simple.

All three births on that page of the registry were “illegitimate”, and named no father. All three mothers were domestic servants.

The witnesses for Archibald and Charlotte were William Taylor and Annie Grubb, respective younger brother and younger sister. Charlotte was in turn the witness for Annie’s wedding to William Sinclair, on the 4th March 1916, the next year. Annie married at 20, and was a domestic servant. Her husband was 18 and a farm servant. William’s parents were Alexander (farm servant) and Christina (m.s. Strachan). Charlotte as witness signed herself Charlotte Taylor. She was nearly 8 months into her pregnancy at the time. I don’t know if her husband was there, or not.

I will mention in passing that my great-aunt Ebeth, unrelated to this family, was far away in Turkey, and also pregnant at the time. She was widowed on May 30th 1916 when her husband, a medical missionary, died from disease caught in his hospital. You can read about her, and how she and her daughter Elizabeth were trapped in Turkey for the duration of the war, elsewhere on Noisybrain.

The information on Archibald and Charlotte’s wedding certificate fits with a birth certificate, giving Archibald’s date of birth as 6th Sep 1892 in Hill-lands of Auchmadies,[2], [3] in Boharm Parish. This location is shown in a ~2018 satellite image and an 1896 map below. Auchmadies lies across the Spey and behind Ben Aigan from the perspective of Rothes. It is north east of Dufftown, on the route from Craigellachie to Keith. The certificate adds that James Taylor and Ann Grant (Archibald’s parents) had been married on 8th Dec 1876 in Mortlach (aka Dufftown) and that James was a ploughman.

The rural Parish of Boharm early in the 19th century had around 300 houses and over 1,000 inhabitants, spread over 25 square miles or so. Incidentally, the old town of Mortlach (Gaelic Mòrthlach) had been expanded and renamed in the 19th century (around 1817) as Dufftown after the Earl of Fife, James Duff, who built housing in the town for soldiers returning home from the Napoleonic Wars. Duff (1776-1857) had been a general for the Spanish in their wars against Napoleonic France. Dufftown (aka Mortlach, aka the “Malt Whisky Capital of the World”) and Rothes were and still are major centres for whisky industry, and have an interesting and colourful history, including Dufftown’s clock: the clock from Banff that hanged a man. Mortlach is also one of the oldest Christian sites in Scotland, with a church founded by St. Moluag, originally from Ulster, who founded an abbey on the Isle of Lismore in Argyll: he was Lugaid of Les Mór. Lismore is the home of my maternal family, and Moluag a familiar name to us. Moluag spoke Pictish as well as Gaelic (and Latin, of course), so was active in the Scottish north east. He lived to an extreme old age and died in Rosemarkie on 25 June 592, according to the ancient Annals of Ulster.

Though the war had started, and over a million men had volunteered by January 1915 (remember how much Lord Kitchener wanted them to), Archibald was not one of them. He was still a farm servant when Charlotte bore their son (also named Archibald Taylor, or “Archie”), on 17th April 1916, nearly a year after their marriage. Conscription had recently been introduced, at least for single men, in January 1916 as the passion for volunteering had dissipated. Archibald himself became eligible for conscription not long after his son was born, when the policy was expanded to include married men. I don’t know whether he was conscripted into the 2nd Battalion of the Seaforth Highlanders, or whether he volunteered, but was enlisted in Elgin on April 27th, just ten days after the birth of his son. He may never have seen his son again.

The Seaforth Highlanders were an infantry regiment, the sort often represented in full regimental dress, or marching into battle with a piper. Their motto was Cuidich ‘n Righ (“Aid the King”). The British Empire relied heavily on the military tradition of communities like this. The eastern Highlands of Scotland had a proud fighting history and culture, as witnessed in the founding of Dufftown itself, the names and recruiting grounds of many old and distinguished, British regiments, and the ancient spirit and tenacity that went back hundreds, and thousands of years. These people saw off the Romans, and the Vikings! At the start of the 20th century, the only game in town was to serve in the army of the British Empire, and to be loyal to the British monarchy. Don’t be seduced into thinking all that tartan has any simple nationalist meaning in a modern sense. It’s complicated.

In Dufftown at War, Barry Hodge estimates a huge proportion in the parish of Mortlach served from the very start in 1914: “Using the 1911 census there were 1,404 men resident in Mortlach of whom some 34% volunteered and served. … half of the eligible men served with the other half being reserved or granted exemption on the grounds of their employment.”

The 2nd Battalion fought at the Battle of the Somme in Autumn 1916, but I don’t know if Archibald was there. He probably was. He would surely have been in the Battle of Arras in April 1917 (starting on the 9th), because he was injured in the leg, as recorded in the Morayshire Roll of Honour (1921), on 12th April 1917 (see the links at the end). The battalion also saw action at the Battle of Passchendaele (aka Third Battle of Ypres) in Autumn 1917, the Battle of the Lys in April 1918, the battles of the Hindenburg Line and the final advance in Picardy. Archibald was there during some of these famously bloody and hideous events.

So, when and how did he die?

The Wrong Death

For a while I thought I knew the answer, but I had got confused. I’d found the wrong dead soldier. After all, there are many servicemen recorded as just “A. Taylor”, and several called Archibald. Many were in their mid-twenties. But I had forgotten to use his regiment as a major clue.

The wrong man was Private Archibald Awburn Taylor, a namesake of similar age. He was a soldier (Service number 30360) in the 9th Battalion of the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles). He was killed at Arras in 1917 aged 24. His details provided a reasonable fit, taking into account the year of birth, location, and range of possible dates of death.

Everyone Remembered provided the essential correction. His personal page is here, and it gave the detail I needed: his parents did not match Charlotte’s parents-in-law on her marriage certificate. The site says that he was “Son of L. C. Taylor, of 42, Talbot St., Grangemouth, Stirlingshire, and the late Archibald G. Taylor.” And the regiment didn’t fit.

He was the wrong man. It was the wrong death.

Let’s not ignore him, but. Let’s spend a little time with this accidental namesake, before getting back to the right man. Why not? After all, here he is, listed on the “First World War on this Day” blogspot, a listing that makes the point that he was just one of 7,371 British Empire service personnel killed on the 3rd May 1917. Just on that day. It might help us to understand the enormity of the horror if we spend a just a little unnecessary time on the “wrong man”.

Archibald Taylor, Killed in Action 1917

This other Archibald was almost certainly killed in a major action on the 3rd of May, part of the Battle of Arras, just east of the (beautifully rebuilt) French town of that name. The longer battle lasted from 7th April (after a 4 day bombardment) to 16th May.

“Arras saw the greatest concentration of Scottish battalions in any of the set-piece battles of the war. With the 9th and 15th (Scottish) Divisions and the 51st (Highland) Division, together with a number of Scottish battalions in other Divisions involved, there were a total of 44 Scottish battalions committed to the battle… One-third of the 159,000 casualties were Scottish.”[4]

The specific action that Archibald is likely to have been killed in was called the third battle of the Scarpe:

“Although attacks in late April had seen little gain, with the French Army facing defeat in the south the Allies were pressured to keep the Arras front going. So on 3rd May a further major attack was staged east from Monchy along the River Scarpe valley.”[5] “Although this battle was a failure, the British learned important lessons about the need for close liaison between tanks, infantry and artillery.”

There is a dramatic photograph of the Cameronians at Arras, in April, among first person testimony about trench warfare in general, on the Imperial War Museum’s webpages. The National Library of Scotland adds detail about the photographer.

“John Warwick Brooke, of the Topical Press Agency, was the second British official war photographer to go to the Western Front in 1916. The demands placed on he and his colleague, Ernest Brooks, were heavy. They had to take as many photographs as possible, with as much variety as possible, a difficult task for two men covering an army of over two million. Despite this, Warwick Brooke managed to take what would become some of the most memorable images of World War I. As an officially appointed photographer, Warwick Brooke was assigned to the Western Front to follow the progress of the British Army. During his time there, between 1916 and 1918, Warwick Brooke is estimated to have taken over 4,000 photographs.“

Archibald Taylor, Killed in Action 1918

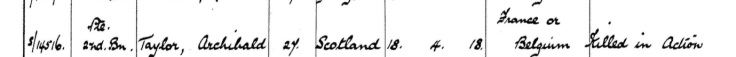

Charlotte’s Archibald Taylor, the right man (but in the wrong place at the wrong time, from their point of view), was service number S/14516 of the 2nd Battalion of the Seaforth Highlanders. He was killed in action probably in France near the border with Belgium on 18th April 1918, at the age of 25. He (i.e. his service number) was a little hard to find, because the age on the collated report and therefore his death record on Scotland’s People says he was 27.[6]

His death was reported in the Weekly Casualty List (War Office & Air Ministry) on Tuesday 4th June 1918 and I think in The Scotsman on Saturday 1st June.

He is commemorated at “Everyone Remembered” (as soldier number 167231), but is only there as Private “A. Taylor”. Those records say his age was unknown, and give no next of kin. The Scottish National War Memorial records him, adding his full first name and place of birth, but the latter transcription has a classic typo: “Bohann” instead of “Boharm”. This transcription error is repeated by FindMyPast, but they add that he served in the 2nd Battalion (“Ross-Shire Buffs”). The Commonwealth War Graves Commission record is online here, lacking his full first name, but the regiment, service number, and date of death fit the other entries, and an entry for next of kin hidden away in a scan of original documentation under Headstone tab seals it (despite another typo, this time on the original): Mrs C. Taylor, 74 High Street, Rothes, Morayshire. The Morayshire Roll of Honour also adds the detail that his mother’s address was 50 Balvenie Street, Dufftown (see the “Links” section at the end for an image and discussion about the errors in his listing).

His name was one of 134,712 projected on to the Scottish Parliament on Armistice Day 2018. The display named all the men and women in the Scottish National War Memorial Roll of Honour who died in World War One.

He was one of 1,371 British Empire service personnel killed on 18th April, 1918.

He was 25 years, 7 months and 12 days old.

He had been married for nearly three years.

He died on the day after his son Archie’s second birthday.

His widow Charlotte married James Munro one year later, to the day, on the 18th April, 1919.

War Diary

The battalion War Diary has a long and detailed entry for the day Archibald was killed, reflecting “a fairly substantial engagement with the enemy”.[7] Around 120 men in the battalion were killed defending a strategic position on a canal (Canal d’Aire à la Bassée probably) at the Bois de Pacaut, near the villages of Hinges, in the face of enemy action. Some companies faced intense and annihilating barrage. The battalion held firm. Their Lieutenant Colonel said: You can rely on my Battalion to stand fast on its front.

The War Diary describes the Battalion undergoing heavy bombardment, and battle raging on both sides of the canal.

April 18th – In the Field

Disposition of the Bn [battalion] before enemy attacks were as follows: A Coy [company] holding line on canal bank from pontoon at W3a79 (inclusive) turning N.W. with posts on north side of canal at Q33c9520 and Q33c68 and at La Pannerie about W4a?8. C Coy from pontoon at W3a79 turning S.E. along canal bank on S. side of canal. B Coy on right of C Coy with platoon pushed out in posts from Pont L’Hinges along road toward La Pannerie. D Coy in support at Le Cauroy. Bn H.Q. at W14b47 S. of Le Cauroy.

Enemy opened a heavy bombardment on back areas and cross roads at 1am. Shelling of west areas continued up till 8.30am. Intense and annihilating barrage was placed on the canal bank from 3-4.15am, which fell particularly heavy on A&C Coys. Enemy were seen massing S.W. out of Bois de Pacaut at 3.45am and at about 4.15am advanced out of the wood towards the canal. About 4.45am he managed to get to the canal and tried to place a pontoon across at W3a88. This attempt failed, being met by very heavy machine and Lewis gun fire and bombing.

D Coy advanced to reinforce C&A Coys on canal bank about 4.45am and on arrival reported to Bn H.Q. that most of party which had been working on A Coys posts previous to the attack had been ferried back over the canal safely. Situation as to advanced posts of A Coy obscure but “illegible word” at Q33c520 and Q33c68 must have been over-run, according to evidence of 2 or 3 survivors who managed to swim back across the canal.

About 5am posts of A&B Coys at La Pannerie were successfully withdrawn by their officers across Pont L’Hinges. They were not attacked but were being fired into from canal bank. At 5.40am an attempt was made by R.E. to blow up Pont L’Hinges. The demolition was unsuccessful and a second and successful attempt was made later in the morning. By 6.15am enemy attacks had been completely defeated and the Bn still held its line. At 4.25am Lt.Col. having “3 illegible words” got a message “illegible word” to Division by visual “You can rely on my Bn to stand fast on its front”. This was completely fulfilled and the line along the canal firmly held.

About 8.30am enemy on N. side of canal came from under cover of bank with their hands up. Some were ferried across, others swam; about 115 prisoners were taken in this way. Throughout the preliminary shelling and the “illegible word” communication was kept by wire between H.Q. and the canal bank and only when it was not of much importance, did the line get broken. Other successful means of communication were by runners who did extremely good work and by “illegible word” from Bn H.Q. to Division. This later means became important when it grew light owing to shell-mist lying over whole area.

Enemy position after the action was inside S. portion of Bois de Pacaut and in La Pannerie farm. Otherwise exactly the same as before, along the whole Bde front. The behaviour of the Bn under the most intense barrage was beyond praise, and the manner in which the Bn dealt with the attempts of the enemy infantry needs no comment. Casualties were 1 officer killed and 3 wounded, 115 other ranks, proportion of “illegible word” not being high. Total casualties might have been expected to be considerably heavier under the circumstances.

A congratulatory wire was received from G.O.C. 4th Division and the following is an extract from a complimentary message sent by the Corps Commander to G.O.C. 4th Division:

2nd Battalion Seaforth Highlanders for their fine endurance under a very heavy bombardment by 5.9 howitzers and for the way in which they subsequently frustrated the enemy’s attempt to cross the canal S. of Pacaut Wood.

Orders were received in the evening for us to send out patrols to a side of canal and in the event of finding S. portion of Pacaut Wood unoccupied by enemy to establish a line of posts along side in wood from Q 33 b 8 3 to Q 33 d 8 5 and to get into touch with brigade on left.

Chocques, France

Archibald’s physical memorial is in Chocques Military Cemetery, Pas de Calais, France. His remains were interred in plot III. A. 12. Many men who died were never found or identified, of course. Some of those continue to be found. The small “Communal Cemetery” at Hinges has military burials from WW2, but also two unidentified soldiers from the 1914-18 War are buried in a joint grave. Their remains were found “a few years ago by a workman excavating the nearby canal.”

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission and other sources provides the following description and information.[8]

“Chocques was occupied by Commonwealth forces from the late autumn of 1914 to the end of the war. The village was at one time the headquarters of I Corps and from January 1915 to April 1918, No.1 Casualty Clearing Station was posted there. Most of the burials from this period are of casualties who died at the clearing station from wounds received at the Bethune front. From April to September 1918, during the German advance on this front, the burials were carried out by field ambulances, divisions and fighting units. The groups of graves of a single Royal Artillery brigade in Plot II, Row A, and of the 2nd Seaforths in II D, and III A, are significant of the casualties of the 4th Division at that time.” “After the Armistice it was found necessary to concentrate into this Cemetery (Plots II, III, IV and VI) a large number of isolated graves plus some small graveyards from the country between Chocques and Béthune.”

The cemetery, 4km north-west of Béthune, was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens and Captain Wilfred Clement Von Berg M. C., and it contains nearly 2,000 graves. Of these, 45 were Seaforth Highlanders. Buried near Archibald in the same plot (III) are nine, all but two killed on that self-same day: Privates G. Falconer, J. Jennings, James L. Ogilvie, Donald Robert Ross Thompson (age 19), Thomas Donoghue (19), J. Flett ( 17th April, age 20), A. Bain (29), Matthew Hutchinson (28), and Captain John Lyon Booth M.C. (25). Plot II, row D reached capacity with nine more: Corporal George Muir (April 17th, age 33), Privates B. Clarke, J. McDonald, A.S. Milne (age 18), S. Gardner (19), Alexander Hay (24), Allan Ellis (19), J. Logan (37), and Donald Norman McLennan (21). Elsewhere are three more: Lance Corporal G. Munro (age 37), Privates Charles Frederick Henderson (20) and W. Kennedy.

That’s a total of 22 Seaforthers lying near Archibald, 20 of them killed on the 18th. However, 120 men in the battalion were killed that day, as noted above, and other died of their wounds. Some were never found or recovered. Others killed that day are buried elsewhere in the area, like Privates Sam Fowlie (age 19), Claude William Tretheway (26) and Albert Tyrell (31), who lie at Le Vertannoy British Cemetery, also at Hinges nearby, a cemetery that was begun in April at the time of this battle, and maybe in the Hinges Communal cemetery, specifically those two unknown soldiers discovered at the canal, mentioned above.

Rothes War Memorial

Even the smallest village in Britain typically has a war memorial. Schools, work-places, town-halls, and other civic memorials name every person associated with an area or institution killed in the the Great War.

The Rothes War Memorial (UKNIWM Ref no: 8724, currently in Seafield Square, Anvil Gardens, Rothes, AB38 7AZ) is pictured online giving full details of all names. See War Memorials Online, Genealogy Junction from the Wakefield Family History Society or the WarMemScot website. The latter site describes it as:

“a freestone mercat cross style memorial in a classical style. The square pedestal with an ogee carved top and fluted pillasters supports a six foot column with roman ionic capital crowned by a unicorn with shield. The memorial was unveiled on Saturday 6th August 1921 by the Countess of Seafield (Ref. The Northern Scot, 13th August 1921). The monument stands at a road junction in North Street at Anvil Gardens.”

The Scotsman newspaper of 8th August 1921 reported:

“The war memorial erected at Rothes (Morayshire) for the 71 men from the parish, who fell in the war was unveiled on Saturday in presence of a large crowd.”

Private Archibald Taylor appears on one of the four WW1 plaques, next to some other Seaforth Highlanders, whose fate, like all the others, can also be found online. Part of my purpose here is to give a sense of the connectedness, randomness, and scale.

Archie Taylor (1916-1944)

Archibald and Charlotte’s son, also Archibald, or “Archie” Taylor, could also be described as my aunt’s elder (half) brother. Born on 17th April 1916, he was was 10 years older than her, and her only older brother. (She had an older sister, born in 1924, just two years older, and many younger siblings.) He would have had a significant role in the family. Charlotte’s marriage to James provided (the hope of) a stable and financially secure home for him from the age of three. Even so, he kept his father’s surname; a man of whom he would have had no personal memories.

In 1940 (on March 8th) Archie’s mother Charlotte died at 66 Land Street Rothes, aged only 50. Archie was the witness informant on her death certificate. His (step) father James (aged 46) would remarry within a year, on 28th February 1941, to Marie Isobel Silk, aged 30. More of that story some other time. Incidentally, James was a sergeant in the 8th Battalion of the Seaforth Highlanders, and gave his address as a military camp at Invergordon on his 1941 wedding certificate.

Archibald served with the 9th Battalion of the Seaforth Highlanders, according to the plaque, but I know even less about him than his father. He appears on the WW2 addition to the Rothes War Memorial, near his father.

As well as her brother Archie, the WW2 plaque names two of my aunt’s uncles. Driver James Munro (Royal Artillery), a namesake of her father, may also be a relative. There are still Grubb and Munro relatives and descendants in the area.

- Private Alexander Grubb (6th Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders, service number 2812041). Alexander was born on 23 April 1901 was killed in Belgium aged 39 on the 31st May 1940. An early newspaper report says “Sergt. Alexander Grubb (39), who was formerly engaged as a maltman at Glengrant Distillery, and is also missing, is the third son of Mrs Grubb, 17 New Street, and the late Mr James Grubb” (Aberdeen Weekly Journal, June 27th 1940). A later report confirmed his death – he died of his wounds.

- Sergeant Charles Grubb (Royal Army Service Corps, service No: T/280385). Charles was born 25 Jan 1903, was married to Jane Anderson on 4th July 1930, and was killed aged 40 on 13 Jan 1944.

Archibald Taylor, Killed in Action 1944

Archie was killed in Italy on 10th Jan 1944. He was 27 years old. Though the Rothes War Memorial says he was (originally) in the 9th Seaforth Highlanders, his Commonwealth War Graves Commission records state he (service number 14209283) served in the 1st Battalion of the (London Scottish) Gordon Highlanders. His identity is confirmed via the statement that he was “Son of Archibald and Charlotte Taylor; stepson of James Munro, of Rothes, Morayshire.” Scotland’s People records his death and family details via the same service records, also giving his service number as #14209283, and specifying which of the many equally depressing causes of death was relevant: “killed in action”. The Scottish National War Memorial gives his affiliation as Gordon Highlanders and the London Scottish.

FindMyPast records provide an entry for Private Archibald Taylor, 14209283, born in Moray and died in Italy on 10/1/1944, serving in The London Scottish (Donside).

It seems the 1st Battalion served “with the second formation of the 51st (Highland) Division (formed by redesignation of the 9th (Highland) Infantry Division” throughout most of the Second World War, serving in North Africa at El Alamein and Tunisia. Their battle honours list for Italy include the landing in Sicily, Anzio, and Rome, as they pursued the Nazi army north. It is likely he was killed in the skirmishes which precipitated the first of four battles for Monte Cassino, which began on January 17th 1944, following suspicion that the Axis forces were using the non-combatant abbey in its “protected historic zone” as an observation post on high ground, due to increasing casualties from pin-point attacks in the area.

He is commemorated at the Cassino memorial, SE of Rome.[9] The Commonwealth War Graves Commission protects this very beautiful cemetery and memorial to over 4,000 personnel. I think the plan gives a better indication of the impersonal planning needed for war cemeteries than an attractive blue skies photo. But we all need blue skies, and every person is, after all, individually memorialised. Archie’s name appears on panel 11, but not on a headstone.

Why is his name on a panel in the centre of the cemetery? “Individuals are commemorated in this way when their loss has been officially declared by their relevant service but there is no known burial for the individual, or in circumstances where graves cannot be individually marked, or where the grave site has become inaccessible and unmaintainable.”

Archie is the last in the list of the men from London Scottish regiment with no known grave. Above him are are listed A.M. Sutherland, J.E. Smith, T.S. Robertson, R. Ricketts … and so on, back to Surnames starting with A. Then there’s another regiment and another panel. And of course, there’s another cemetery, another country, another war.

My opinion of “Remembrance”

All around such war cemeteries, normal life goes on. But the local people are very aware. Many locals are the descendants of the civilians and their relatives and neighbours whose lives were ended or ruined by war. The remembrance is pervasive.

A country over-run by conflict experiences long-lasting and profound effects, but they are not permanent, for good or ill. The effects on nations that primarily fought in a foreign land, and won, will be weaker, and more likely to mutate towards celebration and pride as the memories fade. Perhaps the oral histories and film of WW1 will give it a special power to horrify, alongside its purposelessness and after-effects. It is to be hoped that the political and cultural will to avoid war is bolstered by Remembrance Day. Uncritical and dispassionate remembrance is not enough to prevent a repeat, but it’s a reasonable start. If we can add an appropriate degree of human empathy, regret and revulsion one day a year, that’s to be applauded. Remembrance can become glib, sentimental or worse if guided by narratives of pride and thanksgiving, rather than ones of pain and determination to prevent it all happening again. Only 100 years on, some official ceremonies and expressions of national remembrance still indicate a need for those who remember most and best to listen to those who are reticent to do so. Other more modern and inclusive events and ceremonies have touched hearts more successfully, including 1418now, particularly the weeping poppies. That said, there will always be a central role for our own military in our remembrance, just as we must ensure we remember the suffering of civilians, former allies… and former enemies.

On the lead up to the 11th, film and photos of Macron and Merkel, demonstrate a profound response that I think still embodies their national remembrance in a way that May and Trump and the countries they represent struggle to match. On this weekend, World leaders are in Paris, many of them striving to embed and preserve what have been, until now, largely unquestioned post-war multilateral movements for peace and co-operation. That is a good new centennial move, for those interested in preserving and promoting peace and cooperation. Given the patent rise of authoritarian political leadership around the world, and skepticism about bodies such as the UN, NATO and EU, and in particular the UK’s rejection of the EU, some political leadership at least is using this anniversary in ways I find appropriate.

Standing in Verdun or Dachau as a tourist is a spooky experience that can be repeated at numerous comparable sites all around the world. Imagine living near one. It’s not like being down the road from Hastings. Most countries around the world have sites where the horrors of war and conflict are vivid, devastating and resonant, because they are in a community’s living memory. You can be anywhere, from Cambodia to Gettysburg. You can be near be a battlefield, railway siding or football stadium used for the slaughter of innocents. The fumes of Remembrance are in the air you breathe when you drive past the site of the WW1 trenches in your daily life. The echoes can be heard in the community. That’s why it’s hard on the island of Great Britain to remember the wars of the 20th century in the way that others can: the Battle of Britain was in the air, the Battle of the Atlantic was in the ocean, the effects of the Blitz are barely visible, and our armies fought far from home. The focus is different.

In a war-zone, normal people suffer, and can be driven to selfless, brave or stoic actions which anyone can admire. They might also inflict great suffering on their enemies, whether in defense or in aggression, whether we like it or not. It must surely be easier to appreciate such history on the spot. Place matters. In the absence of the self-perpetuation of complexity, remembrance is more likely to be subject to manipulate simplification by those in control of its institutions. I think this is why our annual ceremonies can repel rather than unite: some of us find parades filled with martial, national and religious symbols to be as offensive as the denial of respect for those who suffered. It’s harder to be unequivocally supportive of our rituals of remembrance given what some of their jingoistic supporters say. But is is usually possible to compromise. You can yank my chain by saying that we owe a contemporary “debt” to participants in conflicts that might usually seen as having achieved nothing, or doing harm, especially if that’s a view of participants. It doesn’t seem respectful to me to say a national “thank you” to the dead.[10]

Honour is due, and compassion, and much else, in relation to WW1. But I can’t see it as disrespectful to say the deaths on both sides were a waste and a mistake, and that no good came from any of it. Let’s separate the service of the individual from the mistakes of those making the decisions. We need to remember the suffering of the innocent alongside a range of amazing human qualities (like fortitude and bravery) which civilians and combatants alike may display, and the historical moral justification for the conflict last, if such things even matter at all. Giving thanks even for the defeat of fascism in WW2 is something for another day. That victory is something that deserves thanks and celebration, but it should not be mixed up with remembrance.

So, contrast the European war cemeteries that pepper the killing grounds in our various “theatres of operation” (and will do so in perpetuity) on the one hand, vs. the cenotaphs and war memorials in Great Britain on the other. France has its local memorials in town squares too. Personally, they induce none of the goose-pimpling emotional deflation and anxiety felt when driving past yet another cemetery among the rolling hills and farmland. It makes me think that is particularly hard to understand warfare in Britain. Our landscape lacks visible battlefields. Our nation tends to fight in wars abroad, and so it’s surely harder to perceive the lessons in all their obvious, in-your-face force. This is why our focus each November is on the services and their ultimate sacrifice. They left their families and homes, and never returned.

There are, however, places and landscapes which can haunt us, even in Scotland. More of that below.

When it comes to the World Wars, we also tend to over-emphasise the suffering on the home front, somewhat. We had rationing, they had starvation and cannibalism. We had militarisation, they had enemy occupation. We had internment, they had death camps and genocide. We had the blitz, they had atomic bombs and total defeat. We had the cold war, they had the iron curtain and the Berlin wall. We had restrictions on free speech, they had fascism. We had air-raid wardens, they had the gestapo or the NKVD. We had dissent, they had revolution. We had challenges to our borders, some of their nations were wiped out. And ultimately, for both those wars, our awareness of world-wide suffering seems to be dulled by the opiate of victory and the lack of education about, and empathy with, other combatants.

We definitely have a rose-tinted positive spin when it comes to a host of post-war social changes. Amongst some reminders that the “returning heroes” suffered long-term trauma and were often excluded from jobs and dissuaded from talking about their experiences, I’ve heard claims that the wars were worth it because they heralded positive changes and trends such as women’s emancipation, labour laws, Irish and Indian independence, decolonisation (eventually), our Blitz spirit, as inspiration for the creative arts, and for heralding the welfare state and even the Swinging Sixties.

So to finish, let’s return to the sort of community from which Archibald Taylor and so many others hailed. An episode of the BBC programme Landward screened a special on April 11, 2014, to explore the effects of World War I on rural Scotland. It was discussed in a blog (and it elicited 70 comments, but seems to be off-line now) at http://www.stronach.co.uk/2014-02-19/filming-on-the-cabrach in which Norman Harper (the author) says some things I think are both very appealing and very important:

“As any self-respecting North-easter knows, The Cabrach is Scotland’s obvious testament to the waste of young life in wartime. The great numbers of tumbledown crofts and steadings you see in that triangle bounded by Dufftown, Rhynie and Lumsden happened not because of land policy or the Depression or a series of bad farming years. They happened because virtually all the fighting-age men and boys went off to war in 1914. Many did not return. They believed politicians and newspaper leader-writers who said that the more men who joined up, and the quicker they did it, the sooner the enemy would be defeated and the earlier they could be home. It was the original “home by Christmas”.

We all know now that it didn’t happen that way. Many died either in battle or because they succumbed to measles, to which they had no immunity because they came from such a self-contained community.

The women, children and old folk they had left behind to keep the crofts ticking over for the implied four months could not survive beyond a second Cabrach winter and eventually had to find accommodation and work elsewhere. They abandoned the crofts, and what you see a century later was once described by a Dutch academic historian as ‘the biggest war memorial in Europe’.”

While I agree with the general thrust, I need to disagree, however, with that academic. So would most people who have been to the Western Front, and having read a bit about other countries at the edge of Europe: Greece, Turkey and the Middle East, Russia: there are other contenders with their own empty or “ethnically-cleansed” landscapes. And think also of places in Japan, Sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa, India and Afghanistan, China and South America. Ask them about their missing generations. But yes, there are various places in Britain you can go to where you can hear the silence caused by war, if you listen, and the Cabrach is surely one of them. A landscape so different to the trenches of Flanders, or the white-studded green of a war grave cemetery, but one just as able to tell a story of men and communities destroyed as a result of that so-called Great War.

NOTES and SOURCES

[1] Places like Rothes, Aberlour, Keith, Bridgend, Mortlach (in Dufftown), Inveravon (or Inveraven) near Ballindalloch, Advie, Cabrach and Boharm.

[2] Hilllands (sic) of Auchmadies also appears in the 1851 census, and is near map reference NJ324481, according to GENUKI Placenames of Boharm list. Online map GridReferenceFinder. Oh, and here’s Parkbeg too, on the GENUKI Placenames of Mortlach list and the 1887 Ordnance Survey map at NJ333409, a place which appears nowadays to be at the bottom of a quarry. The population figures comes from https://forebears.co.uk/scotland/moray/boharm which cites the Topography of Great Britain, 1802-29, written by George Alexander Cooke

[3] There were 28 births of boys called Archibald Taylor in the relevant 5 year period in Scotland, incidentally.

[4] Quotes in this section are lifted from http://www.theroyalscots.co.uk/823-2/ – here and below, and from Wikipedia, but for more detail it would be advisable to check further, e.g. https://www.forces-war-records.co.uk/units/240/cameronians-scottish-rifles/ (subscription only).

[5] See for example http://ww1centenary.oucs.ox.ac.uk/battle-of-arras/the-battle-of-arras-an-overview/ or http://www.longlongtrail.co.uk/battles/battles-of-the-western-front-in-france-and-flanders/the-arras-offensive-1917-battle-of-arras/

[6] National Records of Scotland, 128/AF/ 265, accessed from Scotland’s People.

[7] The transcription was made by user sgmcgregor and posted online in September 2010 at https://www.greatwarforum.org/topic/152254-2nd-battalion-seaforth-highlanders/ – the short quote that it was a fairly substantial engagement was the transcriber’s opinion, based on knowledge of the war diaries. Certainly, most entries are just a couple of sentences. The original War Diary is available from the National Archives. http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C14016967 See also discussion of Bois de Pacaut at https://www.greatwarforum.org/topic/96403-pacaut-wood/

[8] https://www.ww1cemeteries.com/chocques-military-cemetery.html http://www.inmemories.com/Cemeteries/choques.htm and

https://www.cwgc.org/find-a-cemetery/cemetery/16500/chocques-military-cemetery/

[9] https://www.cwgc.org/find-a-cemetery/cemetery/2005600/cassino-memorial/

[10] The UK government has organised “A Nation’s Thank You – the People’s Procession“. They say “On 11 November 2018, members of the public will have a unique opportunity to take part and pay their respects to all those that served in the First World War. The Nation’s Thank You procession will allow 10,000 members of the public, selected by random ballot, to join a procession past the Cenotaph, to pay their respects and help express the nations thanks to the generation that served, and those that never returned.”

LINKS

There are a host of official and volunteer resources out there, with detailed, official, and verified information. And the odd mistake, for a variety of reasons, which of course are being corrected. I have found the following sites useful, interesting, and humbling.

The focus of course is on the UK, Commonwealth and associated forces (in those days, the British Empire), on the Western Front. One of the things we must never forget is that WW1 was much, much more complex than the mainstream domestic narrative of recent times. It was a war of Empires, and many monarchies and empires disappeared abruptly and forever, symbolic of the enormous changes under way. The British experience, though brutal, sometimes appears rather exaggerated in comparison to what other nations lost through war, occupation, revolution, disease, exploitation, coercion, genocide and the destructive international political ambitions of both “winners” and “losers” during the rest of the 20th century and beyond. Wherever you look, there’ll probably be something huge and important about which you had no idea.

- The Commonwealth War Graves Commission https://www.cwgc.org/

- The Scottish National War Memorial https://www.snwm.org/ to search their Roll of Honour

- First World War – On this dayhttps://firstworldwaronthisday.blogspot.com/2014/08/why-do-this.html

- Everyone Remembered https://www.everyoneremembered.org/

- Wikipedia, of course.

- The Royal British Legion https://www.britishlegion.org.uk/

- The Imperial War Museum https://www.iwm.org.uk

- Cabrach – http://www.stronach.co.uk/2015-08-24/cabrach-remembers-its-war-dead

- A Street Near You – https://astreetnearyou.org/ mapping home locations of the dead

- Challenges in matching a name on a War Memorial with the correct military record – by Margaret Frood at this bit of her website

- The dramatic photograph of the raiding party in the trench can be purchased from the IWM shop, and it and many other amazing, sobering and fascinating images are available online there. It’s described thus: “A raiding party of the 10th Battalion, Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) waiting for the signal to go. John Warwick Brooke, the official photographer, followed them in the sap, into which a shell fell short killing seven men. Near Arras, 24 March 1917.” “Fell short” means it was one of our own shells.

- https://www.forces-war-records.co.uk/units/230/seaforth-highlanders/

- The Highlanders Museum, Fort George.

- Last Man Standing: The Memiors of a Seaforth Highlander during the Great War (2012) by Norman Collins, edited by Richard van Emden. Pen and Sword Publishers. His oral history is also in the IWM.

- The National Archives (UK).

- The National Records of Scotland, via Scotland’s People.

- Seaforth service number sequencing described here. Now I know about the “S/”

- Boharm family history https://forebears.co.uk/scotland/moray/boharm

- Scotland’s War http://www.scotlandswar.ed.ac.uk/scotland for Moray Region.

- The Morayshire Roll of Honour was something I saw online only after finding out almost everything: that’s probably always the way! But in some ways, this is just as well. Archibald (1892-1918) is on page 445, but the entry repeats the pervasive error (or his lie?) about his date of birth (7/9/1890 instead of 8/9/1892). There is even a typo relating to his place of death: “Chorquec” as a typo for Chocques. But it does supply his mother’s name, and his Boharm birthplace. So far, this is the only source of information providing his enlistment and his injury.

- The Cabrach Trust https://www.cabrachtrust.org/

- The BBC Scotland programme Landward had another WW1 episode, on 10/11/2018, with a segment from Lewis, looking the lack of crofts post-war (and coincidentally there was a segment revisiting the Cabrach, with a Cold War focus). 18/19 season, programme 20.

- The Western Front Way, a proposed 1000km long-distance walk tracing the front line.

My links

- I have a tag on Noisybrain for WW1 if you want to search further on that topic. There are some completely different stories – from my father’s Scobbie family, for example, like Ebeth’s mentioned in the text.

- In fiction, I recommend Lewis Grassic Gibbon’s Sunset Song and James Robertson’s And the Land Lay Still.

Leave a comment